Key Takeaways

China has transformed itself from an isolated backwater to one of the world’s great economic powers. In conjunction with China’s rise, Chinese companies have emerged as among the largest and most influential in the global marketplace.

China surpassed the U.S. as the leader on the Fortune list in 2020 and today has 136 companies representing 31 per cent of the list’s total revenue.

Over the past four decades, China has transformed itself from an isolated backwater to one of the world’s great economic powers. In conjunction with China’s rise, Chinese companies have emerged as among the largest and most influential in the global marketplace.

In 2000, the Fortune Global 500 was led by the U.S. with 179 companies while China was represented by only ten businesses, as detailed in the data visualization below titled Fortune Global 500 Country Ranking. China surpassed the U.S. as the leader on the Fortune list in 2020 and today has 136 companies representing 31 per cent of the list’s total revenue.

Over the same period, however, the Chinese stock market failed to keep up with the rise of the nation’s corporates.

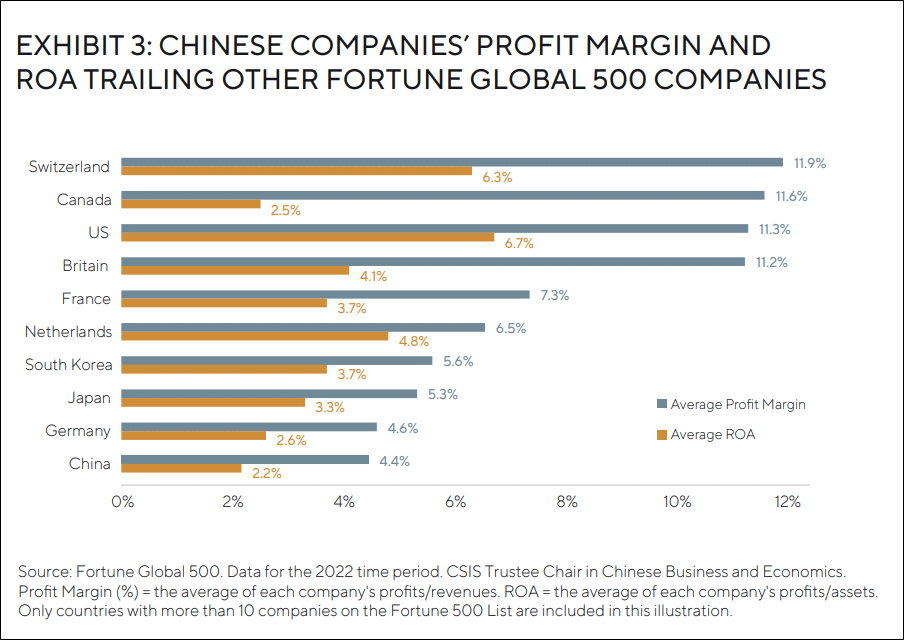

A closer look at the Fortune Global 500 list shows that Chinese companies have been significantly trailing other countries in terms of profit margin and return on assets, according to a recent analysis by the Center for Strategic & International Studies.1 The average profit margin at these top Chinese companies was around one third of that posted by American and many European companies. In our view, the primary driver here is likely a business mix – Swiss pharmaceuticals, U.S. technology innovators being generally more profitable than Chinese state-run banks or grid operators – but a more subtle cause may be the increasingly heavy hand of Chinese regulators emphasizing the Communist Party’s goals.

Over time, Beijing’s obsession with control over the economy and growing involvement in its private sector, have increasingly become a drag to the nation’s corporate champions. This risk has been highlighted by the latest wave of regulatory crackdowns on some of China’s most dynamic industries, ranging from property developers to internet platforms and education companies.

While these actions appeared abrupt and unanticipated – and all seemed to have a regulatory rationale on a case-by-case basis – a look at China’s contemporary history would suggest otherwise. We believe the distorting hand of the Chinese state has always been there.

PRIVATE SECTOR’S ILLUSION

If history offers any guide, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) penchant for cracking down on the private sector is longstanding and often serves the purposes of the government. While investors may have previously viewed these clampdowns as a cost of doing business in China, the risks appear to be rising thanks to the country’s worsening economic, demographic, and geopolitical profiles.

A vibrant private sector is the hallmark of a market economy. Successful businesses serve as the engine of growth, driving innovation, creating jobs, and paying taxes that finance the investment that boosts the broader economy. Over the past four decades, China’s private sector has grown dramatically, as its economy moved away from central planning and policymakers introduced reforms to its state sector. Today, private firms already account for more than 60 per cent of GDP and 80 per cent of the country’s employment.2

The success of these companies and the quality of the entrepreneurship found in China are unquestionable. However, the idea that these can truly be considered independent private companies has been put to the test – and as of now seems to be failing.

The Chinese authorities have long used various financial and administrative tools, such as access to credit and government approvals, to keep a tight rein on the private sector. Companies that failed to fall in line with the party orders were met with a swift and harsh response, while their founders often ended up in prison or disappeared altogether.

Not surprisingly, private firms have learned how to ingratiate themselves with the government, with many forming partnerships with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or offering shares in their firms to government officials.

In recent years, particularly under Xi Jinping’s rule, the government has stepped up efforts to increase its control over the private sector – through blanket regulatory and policy changes, or new technologies such as big data. Some of those efforts include:

- A so-called Corporate Social Credit System, launched in 2014, uses large-scale data to determine whether a company can participate in government procurement bids or have access to credit.3

- The National Intelligence Law, which was passed in 2017, requires all firms in China to accede to government demands to provide information and data as authorities deem necessary to protect national security.4

- Pushing private firms to form CCP branches within the companies and pledge funds to support “common prosperity” in recent years.

- In some cases, the government has blatantly asked for “golden shares” in private companies. That was the case with Weibo, a social-media platform with over 580 million active users, and ByteDance, which owns TikTok.5

In the next few sections, we will review, by decade, the recent evolution of China’s brand of capitalism, as well as the convoluted relationship between the Communist Party and China’s private sector.

1980S: A SHORT-LIVED ENTREPRENEURSHIP BOOM

The 1980s are often given scant credit in economic histories of China, but this was the time when many of the dynamics that currently swirl around the world’s second largest economy first became evident. As China emerged from the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, a period filled with violence and chaos, the country’s reformist leaders – Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang – adopted a more liberal approach to support the emerging private sector.

Though the policy changes at the time were “modest,” the Chinese leaders went out of their way to send a clear signal of “an improvement in property rights security,” according to Huang Yasheng, professor of Global Economics and Management at MIT Sloan School of Management and author of “Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State.” For example, the Chinese government returned confiscated bank deposits, bonds, gold, and private homes to people who had been classified as “capitalists” in 1979.

After Mr. Hu took the top office of the CCP in 1981, he quickly endorsed the idea of recruiting party members from the private sector. These gestures helped the government gain credibility among private entrepreneurs, who in turn grew more confident in the safety of their assets and the predictability of the investment and political environments.

For example, Lenovo Group Ltd., which has eventually grown into the world’s largest PC manufacturer, was founded in 1984 by a team of engineers in Beijing; Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., the Chinese telecom equipment producer which was banned by the U.S. government out of national security concerns, was established in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, a former military officer.

Then came the Tiananmen Square Massacre in June 1989. The post-Tiananmen leaders launched a systematic crackdown on the private sector, resulting in a plunge in private sector employment and massive closures of private firms.

Nian Guangjiu, a private entrepreneur who hailed from the impoverished province of Anhui, took the nation by storm in the 1980s by selling Idiot’s Sunflower Seeds, a popular snack. At one point, Mr. Nian’s business was among the biggest companies in China, hiring hundreds of people and pocketing millions of yuan in profit a year. His fate reversed in September 1989 when he was arrested on charges of corruption and embezzlement of state property. Though the verdict was overturned by the intermediate court in Anhui, his company was shut down by the local government in 1990. Eventually, he was sentenced to three years in prison for having had “immoral relationships” with multiple women, putting a sudden end to a once sensational brand of Chinese capitalism.6

By the early 1980s, millions of entrepreneurs started small-scale businesses in industries such as food processing and construction materials. Today, many of China’s leading manufacturers can trace their roots back to that decade.

Professor Huang noted that the Chinese experiment in the 1980s was nothing short of extraordinary given the country’s political reality. “ A policy approach based on learning by doing may be technically simple and straightforward, but it requires a massive dose of self-constraint on the part of the policy makers. Policy makers have to learn to hone into the realities on the ground rather than imposing their own visions. In an unconstrained political system, that the policy makers were willing to let peasants experiment and to trust them to come up with the right solutions is nothing short of extraordinary,” he wrote in his book.7

Though the 1980s are mostly remembered for the Tiananmen crackdown, the decade is better understood as the first one in which the Chinese government exhibited the two-headedness that has since left so many Westerners confused: An increasing acceptance of openness alongside sudden, unpredictable, often heavy-handed suppression of supposed “enemies.”

1990S: GROWING AGAINST SOE REFORM

The political assault on the private sector fizzled out after Deng Xiaoping’s famous “Southern Tour” in 1992, when the late Chinese leader spoke to reinforce the implementation of his “Reforms and Opening-Up” policy. Following Mr. Deng’s speeches, Chinese leaders Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji overhauled the country’s SOEs, signaling a shift to state capitalism.

In 2000, China’s General Secretary unveiled the doctrine of “Three Represents,” which could be viewed as an official recognition of the growing importance of the private sector in the society.

As the state concentrated its resources to support a group of elite SOEs to play a pivotal role in domestic and international markets, the private sector faced increasing policy and credit obstacles. Despite the adverse environment, China’s private entrepreneurs managed to grow. As many of the smaller, poorly run SOEs were wound down, some turned into privately owned companies via management buyouts. Many became more politically active by lobbying individually or through industry groups. Some entrepreneurs joined local or national People’s Congress and started engaging in philanthropy.

Though the government produced a number of nominal reforms and capitalism became more acceptable around the country during the 1990s, it became clear that those participating in business would be expected to tread carefully on their relationship with the government.

As the Chinese government enhanced the political status of private entrepreneurs by touting their importance, they failed to secure their property rights through institutional reforms, leaving the door open for a slew of high-profile crackdowns on private businesses during the decade.

Take Jianlibao Group, one of China’s largest soft drink producers based in Sanshui, Guangdong, which was spun off from the government owned Sanshui Distillery. For many years, Jianlibao was effectively run as a private sector firm and the local government respected the control rights and its founder Li Jingwei, a former director of Sanshui Distillery. By 1996, Jianlibao’s sales reached six billion yuan and its market share exceeded that of Coca-Cola and Pepsi combined in China. At its heyday, the company contributed nearly half of the tax revenue for Sanshui. It even set up a U.S. office in New York City’s Empire State Building, aiming to take on American consumers. As the company grew, the government’s helping hand turned into a grabbing hand. Seeing sales slowdown, the Sanshui government decided to sell its entire stake in the company, essentially pushing Mr. Li out. Mr. Li was later sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment for embezzlement.8

2000S: THE RISE OF STATE CAPITALISM

In 2000, China’s General Secretary Jiang Zemin unveiled the doctrine of “Three Represents,” clarifying that the CCP should represent the interests of the overwhelming majority of the people of China. This essentially has opened the door to increase the representation of private business executives in the CCP – an official recognition of the growing importance of the private sector in the society.

China’s growth model became increasingly reliant on investment, as the leadership sought to boost the economy by building large-scale infrastructure and urban investment projects. With the 2008 summer Olympic Games scheduled to take place in Beijing, the investment boom reached a frenzied level and China enjoyed a double-digit GDP growth rate almost every year during the decade. The government realized it could mobilize a huge amount of resources and capital through SOEs within a very short period of time, whereas it would take years for private businesses to complete the investments.

However, much of the growth was induced by the government, rather than by market forces, raising questions over its long-term impact on productivity and the environment.

On the heels of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the CCP had begun to manipulate how private companies ran their businesses. Starting that year, every private sector firm with at least three CCP members among its employees was required to have a party unit to “firmly implement the Party’s line, principles, and policies” as the Constitution of the CCP stipulates.9

The State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, established in 2003, further cemented the advantage of SOEs by expanding the areas where state capital should take a controlling stake and excluding private operators from certain industries. As a result, many private companies found it increasingly difficult to get loans from banks, even when massive stimulus packages were rolled out by the central government.

The skeptics were quelled in 2008 as the Global Financial Crisis hit. The struggles of the Western economic model during that period prompted the Chinese authorities to reassess which economic model they wanted to pursue. SOEs came to be seen as keeping China growing and maintaining employment as global trade was collapsing. Many private firms failed, triggering takeovers by SOEs. China’s reliance on state capitalism was ratified.

Ironically, China’s SOEs did not become stronger in our opinion even as they grew in size. As SOEs received more government support, the expectation was for them to fulfill more “national services.”

China’s four largest state-owned banks, which are among the world’s largest by assets, started to see their price to earnings ratios decline in the late-2000s. As China unleashed a massive stimulus package to rescue the economy during the financial crisis, state-run banks were given more detailed guidance on which industries or companies to lend to, and even at which interest rates. The increased control has led to concerns of lower returns and higher non-performing loans at these banks. Since then, Chinese banks have been trading at much lower multiples than their global peers.

Similarly, China Telecom, the country’s largest telecom carrier, completed a record-breaking IPO in Hong Kong and New York in 1997, raising $4 billion from foreign investors who were captivated by the opportunities from China’s growing middle class, freely allocated spectrums, and the government’s plans to restructure the state-owned assets.10 However, investors soon learned China’s telecom carriers are supposed to help the government to “implement faster connectivity and make it more affordable for consumers,” essentially preventing these companies from raising prices despite their heavy investments on the 4G and 5G networks.11 Years later, these once-touted SOEs all have been de-rated to trade as public utilities.

Yet, one group of private entrepreneurs seemed to be thriving: real estate tycoons. As the urban population expanded, China created a nationwide housing market boom. By 2010, the sector’s contribution to China’s GDP surpassed that of all manufacturers, reaching 36 per cent. Some property moguls, such as Wanda Group’s Wang Jianlin, became the country’s richest people and started a buying spree outside the country.12

2010S – PRESENT: INCREASED POLITICAL OVERSIGHT

The party continued to exert its control over the private sector in the 2010s, requiring foreign-invested firms and even NGOs to set up party branches. Official figures show that the proportion of private enterprises with internal party units has grown from 36 per cent in 2012 to 48 per cent in 2018.13

In the summer of 2017, some of the property tycoons’ fate reversed, after China’s State Council issued a notice by several ministries on further guidance and regulation of overseas investment. The guidelines prohibited companies from buying properties, hotels, movie theaters, and other entertainment assets, while outbound investments in upgrading national research and manufacturing industries were encouraged. Moreover, it called on those firms to join the construction of projects in the “Belt and Road Initiative,” an ambitious initiative launched by President Xi that aims to stretch China’s influence around the globe. State banks were required to “reassess” the risk of their lending to property developers who were active in outbound investment.14

Wanda Group’s stocks and bonds plummeted following the new rules, and its founder Mr. Wang quickly sold all the hotels and other entertainment-related assets in a fire sale to pay down its debt. The outcome was much worse for Anbang Insurance Group, which made its name by its nearly $2 billion purchase of the famed Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York. Anbang ended up being dismantled and eventually got absorbed by a number of state-owned firms. Anbang’s former chairman Wu Xiaohui was sentenced to 18 years of imprisonment on charges of fraud and embezzlement.15

Despite the real-estate upheaval, one industry nearly escaped Chinese regulators. Funded by international capital rather than loans from state-run banks, China’s internet platforms grew quickly into corporate giants. In 2014, Hangzhou-based Alibaba Group raised $25 billion from the New York Stock Exchange, making it the world’s largest IPO at the time. The Chinese company owed its success to Softbank founder Masayoshi Son’s initial investment of $20 million back in 2000.16

When Alibaba’s fintech unit Ant Group was poised to raise $37 billion from both Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges in November 2020, the Chinese government stamped it out on the eve of its gigantic IPO, citing “regulatory concerns.” It remains unclear what drove the government’s abrupt action, but we believe that the fear of Alibaba’s growing political clout and possession of sensitive personal financial data might have played a role. The regulator eventually slapped a record $2.8 billion fine on Alibaba Group after an anti-monopoly probe found it abused its market dominance.17

Andrew Batson, director of China Research for Gavekal Dragonomics, an independent research firm, argued that the Chinese internet sector was a regulatory exception as the government had allowed for its growth with a light touch in the early days. Regulators were also perplexed by the nature of many of their novice businesses. However, when these companies became such an important part of the economy, the government decided that they deserved more oversight. What the government did was simply “to bring the internet sector in line with the rest of the economy,” he added.

Less than a year later, China’s $120 billion after-school tutoring industry was nearly crushed overnight by a set of strict new regulations issued by the central government to ban all for-profit tutoring in core education, in order to “ease the burden of excessive homework and off-campus tutoring for students.”18

China’s education system is exceptionally competitive, a problem exacerbated by the previous one-child policy, which put undue pressure on children to excel at schools and support their families. The stringent rules came shortly after China’s latest census results showed that the country was aging even more rapidly than previously thought, prompting Beijing to take the action to alleviate costs for families and encourage them to have more children.

Meanwhile, the crackdown on property developers picked up pace again in 2020. Deeming these heavily indebted companies as a risk to the financial system, the Chinese government rolled out the “three red lines,” a set of debt guidelines that developers must adhere to or face restrictions on their ability to borrow further. Many large developers, most notably Evergrande Group, fell into financial distress afterward.

While these actions all appeared to have a reasonable regulatory rationale on a case-by-case basis, they clearly represented a dramatic step-up of the government’s oversight of the private sector. Internet platforms and property development “are the only two parts of the Chinese economy where private entrepreneurs were able to extract huge amounts of personal wealth and accumulate a lot of power outside the political system,” said Mr. Batson. “Maybe that is a problem in and of itself.”

CONCLUSION

We believe many of China’s current economic malaises – a lack of private investment, falling productivity, and slumping confidence – all stem from declining private business dynamism. The latest wave of crackdowns has further revived fears among private entrepreneurs about a government that is unconstrained by institutional checks and balances, and China’s lack of constitutional protection of property rights.

While the government for now has been put on the back foot by problems like slower post-Covid growth, mounting local government debt, and demands for more from the populace, the temptation to take extreme actions seems to be brewing as conditions continue to deteriorate.

As China abruptly dropped its rigorous zero-Covid curbs and started to refocus on economic growth, the government began trying to woo the private sector again. At the World Economic Forum in Davos early this year, Vice Premier Liu He vowed that “China is coming back” and “ we will keep opening up and supporting private businesses.”19 The newly-appointed premier Li Qiang in March also pledged during his debut news conference that private sector companies would be treated equally with state-owned companies and that the property rights and other interests of entrepreneurs would be strictly respected.

Whether China’s private entrepreneurs and the global investment community will fully buy into that promise remains to be seen – as does whether the government will indeed keep its word. Recent cases such as the disappearance of top tech banker Bao Fan certainly did not help the government gain credibility among the business community. In our view, the dynamics in recent years show that the government’s interactions with private business tend to be essentially countercyclical – aggressive when the economy is doing well, cautious when growth slows down.

The latest wave of crackdowns on private businesses has further revived fears about a government that is unconstrained by institutional checks and balances, and about China’s lack of constitutional protection of property rights.

We believe the lack of policy continuity shows that there are still important institutional and reform gaps China needs to address to ensure a high-quality and sustainable growth path.

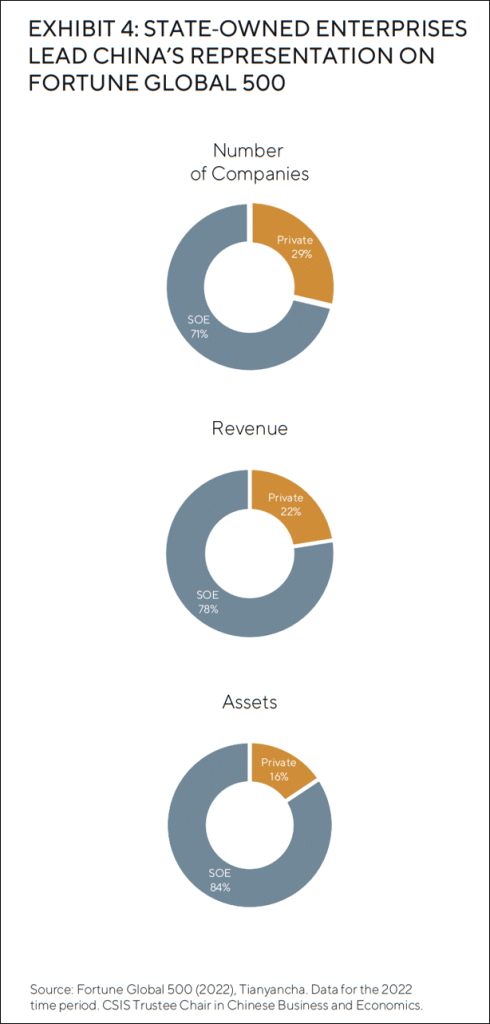

Assessing investment risks is what we do at GQG Partners. While it seems tempting to chase the China re-opening rally, we believe risk for China investments has gone up. China is currently facing multiple long-term challenges, including its deteriorating demographics, growing tensions with the U.S. and its allies, as well as the rest of the world’s increasing re-shoring away from China. If history teaches us anything, we believe it is that now is the time to take a cautious approach in China. As a result, we prefer companies that are aligned with government interests, especially SOEs, that have continued state support and reasonable valuations.

Under Xi’s rule, China appears to have doubled down on its state sector, aiming to promote SOE reforms and maximize their value from their industry leadership. 2023 marks the first time that SOEs will have return on equity and operating cash flow as part of their KPIs, while also being allowed to raise leverage.

As for the private enterprises, especially those perceived as China’s tech darlings, in our view it is difficult to justify the current valuations as it seems many investors have bought into the narrative that Beijing is no longer a threat to these companies. We may change our view if at some point policymakers take a cue from the CCP leaders in the 1980s to keep their hands off the private sector or if valuations become more aligned with the current setting. For now, we remain selective and cautious in China.

DEFINITIONS

Golden shares allow the government to monitor corporate governance and business decisions, particularly at social media firms that influence public opinion.

The National People’s Congress (NPC) is the national legislature and constitutionally the supreme state authority of the People’s Republic of China.

END NOTES

1Qin (Maya) Mei. Fortune Favors the State-Owned: Three Years of Chinese Dominance on the Global 500 List. Center for Strategic & International Studies, Oct. 7, 2022.

https://www.csis.org/blogs/trustee-china-hand/fortune-favors-state-owned-three-years-chinese-dominance-global-500-list

2Economic Daily. The private economy moves towards a broader stage Mar. 30, 2022.

https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-03/30/ content_5682332.htm

3State Council Notice Concerning Issuance of the Planning Outline for the Establishment of a Social Credit System. Jun. 14, 2014.

https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-06/27/content_8913.htm

4The National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic of China. Jun. 12, 2018.

https://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/201806/483221713dac4f31bda7f9d951108912.html

5Tim Culpan. China’s Golden Shares Trade Visibility for Stability. Jan. 17, 2023.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-01-17/golden-shares-offer-stability-less-visibility-after-china-crackdown

6End of an Era: Businessman Nian Guangjiu Passed Away. Jan. 13, 2023.

https://finance.sina.com.cn/jjxw/2023-01-13/doc-imxzyzcq2185991.shtml

7Yasheng Huang. Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State. P. 91. P. 104-105.

8The loser of the state-owned enterprise restructuring: Tragic Li Jingwei – a person who can’t see the morals of the world. Apr. 27, 2013. China Business Paper.

http://shipin.people.com.cn/n/2013/0427/c85914-21301702.html

9Yi-Zheng Lian. China, the Party-Corporate Complex. The New York Times, Feb. 12, 2017.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/12/opinion/china-the-party-corporate-complex.html

10Goldman Sachs, China Telecom Privatization Shines through the Shadow of the Asian Financial Crisis.

https://www.goldmansachs.com/our-firm/history/moments/1997-china-telecom-privatization.html

11The Prime Minister once again mentioned network speed increase and fee reduction! Resolutely rectify the broadband monopoly of commercial buildings and forcibly increase prices, Apr. 8, 2021.

http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-04/08/content_5598498.html

12How much of China’s GDP is dependent on real estate? Oct. 11, 2021.

https://www.zhihu.com/question/300425251

13Dexter Tiff Roberts. May. 7, 2021. The risky logic behind China’s economic strategy: ‘Politics in command.’ Atlantic Council.

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-risky-logic-behind-chinas-economic-strategy-politics-in-command/

14China Publishes Guidelines on Overseas Investments. Investment Policy Hub Aug. 4, 2017.

https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-policy-monitor/measures/3103/china-china-publishes-guidelines-on-overseas-investments

15Maggie Zhang, Xie Yu, and Jun Mai. Anbang’s ex-chief Wu Xiaohui sentenced to 18 years behind bars for US$12 billion fraud, embezzlement. South China Morning Post. May 10, 2018.

https://www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/2145458/anbangs-ex-chief-wu-xiaohui-sentenced-18-years-behind-bars-us12

16Liyan Chen, Ryan Mac, and Brian Solomon. Alibaba Claims Title For Largest Global IPO Ever With Extra Share Sales. Forbes Sept. 22, 2014.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanmac/2014/09/22/alibaba-claims-title-for-largest-global-ipo-ever-with-extra-share-sales/?sh=68ee8ec817c7

17Raymond Zhong. China Fines Alibaba $2.8 Billion in Landmark Antitrust Case. The New York Times. Apr. 9, 2021.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/09/technology/china-alibaba-monopoly-fine.html

18Alexander Chipman Koty. More Regulatory Clarity After China Bans For-Profit Tutoring in Core Education. China Briefing Sept. 27, 2021.

https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-bans-for-profit-tutoring-in-core-education-releases-guidelines-online-businesses/

19Davos 2023: Special Address by Liu He, Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic of China. World Economic Forum. Jan. 17, 2023.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/davos-2023-special-address-by-liu-he-vice-premier-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china/

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

The information provided in this document does not constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made based on it. Neither the information contained in this document or in any accompanying oral presentation is a recommendation to follow any strategy or allocation. In addition, neither is a recommendation, offer or solicitation to sell or buy any security or to purchase of shares in any fund or establish any separately managed account. It should not be assumed that any investments made by GQG Partners LLC (GQG) in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of any securities discussed herein. Before making any investment decision, you should seek expert, professional advice, including tax advice, and obtain information regarding the legal, fiscal, regulatory and foreign currency requirements for any investment according to the law of your home country, place of residence or current abode.

This document reflects the views of GQG as of a particular time. GQG’s views may change without notice. Any forward-looking statements or forecasts are based on assumptions and actual results may vary. GQG provides this information for informational purposes only. GQG has gathered the information in good faith from sources it believes to be reliable, including its own resources and third parties. However, GQG does not represent or warrant that any information, including, without limitation, any past performance results and any third-party information provided, is accurate, reliable or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. GQG has not independently verified any information used or presented that is derived from third parties, which is subject to change. Information on holdings, allocations, and other characteristics is for illustrative purposes only and may not be representative of current or future investments or allocations.

Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Performance may vary substantially from year to year or even from month to month. The value of investments can go down as well as up. Future performance may be lower or higher than the performance presented and may include the possibility of loss of principal. It should not be assumed that investments made in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of securities listed herein.

The information contained in this document is unaudited. It is published for the assistance of recipients, but is not to be relied upon as authoritative and is not to be substituted for the exercise of one’s own judgment. GQG is not required to update the information contained in these materials, unless otherwise required by applicable law. No portion of this document and/or its attachments may be reproduced, quoted or distributed without the prior written consent of GQG.

GQG is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Please see GQG’s Form ADV Part 2, which is available upon request, for more information about GQG.

Any account or fund advised by GQG involves significant risks and is appropriate only for those persons who can bear the economic risk of the complete loss of their investment. There is no assurance that any account or fund will achieve its investment objectives. Accounts and funds are subject to price volatility and the value of a portfolio will change as the prices of investments go up or down. Before investing in a strategy, you should consider the risks of the strategy as well as whether the strategy is appropriate based upon your investment objectives and risk tolerance.

There may be additional risks associated with international and emerging markets investing involving foreign, economic, political, monetary, and/or legal factors. International investing is not for everyone. You can lose money by investing in securities.

Where referenced, the title Partner for an employee of GQG Partners LLC indicates the individual’s leadership status within the organization. While Partners hold equity interests in GQG Partners Inc., as a legal matter they do not hold partnership interests in GQG Partners LLC or GQG Partners Inc.

GQG Partners LLC is a wholly owned subsidiary of GQG Partners Inc., a Delaware corporation that is listed on the Australian Securities Exchange.

INFORMATION ABOUT BENCHMARKS

Net total return indices reinvest dividends after the deduction of withholding taxes, using (for international indices) a tax rate applicable to nonresident institutional investors who do not benefit from double taxation treaties.

Information about benchmark indices is provided to allow you to compare it to the performance of GQG strategies. Investors often use these well-known and widely recognized indices as one way to gauge the investment performance of an investment manager’s strategy compared to investment sectors that correspond to the strategy. However, GQG’s investment strategies are actively managed and not intended to replicate the performance of the indices: the performance and volatility of GQG’s investment strategies may differ materially from the performance and volatility of their benchmark indices, and their holdings will differ significantly from the securities that comprise the indices. You cannot invest directly in indices, which do not take into account trading commissions and costs.

The S&P 500® Index is a widely used stock market index that can serve as barometer of US stock market performance, particularly with respect to larger capitalization stocks. It is a market-weighted index of stocks of 500 leading companies in leading industries and represents a significant portion of the market value of all stocks publicly traded in the United States.

The Shanghai Composite Index measures the value of all stocks (A-shares and B-shares) traded on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The index is unmanaged and does include the effect of fees.

NOTICE TO AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND INVESTORS

The information in this document is issued and approved by GQG Partners LLC (“GQG”), a limited liability company and authorised representative of GQG Partners (Australia) Pty Ltd, ACN 626 132 572, AFSL number 515673. This information and our services may only be provided to retail and wholesale clients (as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)) domiciled in Australia. This document contains general information only, does not contain any personal advice and does not take into account any prospective investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. In New Zealand, any offer of a Fund is limited to ‘wholesale and retail investors’ within the meaning of clause 3(2) of Schedule 1 of the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013. This information is not intended to be distributed or passed on, directly or indirectly, to any other class of persons in Australia and New Zealand, or to persons outside of Australia and New Zealand.

NOTICE TO CANADIAN INVESTORS

This document has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not an offering memorandum nor any other kind of an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, instrument or investment product or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It is not intended and should not be taken as any form of advertising, recommendation or investment advice. This information is confidential and for the use of the intended recipients only. The distribution of this document in Canada is restricted to recipients in certain Canadian jurisdictions who are eligible “permitted clients” for purposes of National Instrument 31-103 Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations.

NOTICE TO SOUTH AFRICAN INVESTORS

Investors should take cognisance of the fact that there are risks involved in buying or selling any financial product. Past performance of a financial product is not necessarily indicative of future performance. The value of financial products can increase as well as decrease over time, depending on the value of the underlying securities and market conditions. The investment value of a financial product is not guaranteed and any Illustrations, forecasts or hypothetical data are not guaranteed, these are provided for illustrative purposes only. This document does not constitute a solicitation, invitation or investment recommendation. Prior to selecting a financial product or fund it is recommended that South Africa based investors seek specialised financial, legal and tax advice. GQG PARTNERS LLC is a licenced financial services provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) of the Republic of South Africa, with FSP number 48881.

NOTICE TO UNITED KINGDOM INVESTORS

GQG Partners LLC is not an authorised person for the purposes of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 of the United Kingdom (“FSMA”) and the distribution of this document in the United Kingdom is restricted by law. Accordingly, this document is provided only for and is directed only at persons in the United Kingdom reasonably believed to be of a kind to whom such promotions may be communicated by a person who is not an authorised person under FSMA pursuant to the FSMA (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 (the “FPO”). Such persons include: (a) persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments; and (b) high net worth bodies corporate, partnerships, unincorporated associations, trusts, etc. falling within Article 49 of the FPO. The services provided by GQG Partners LLC and the investment opportunities described in this document are available only to such persons, and persons of any other description may not rely on the information in it. All, or most, of the rules made under the FSMA for the protection of retail clients will not apply, and compensation under the United Kingdom Financial Services Compensation Scheme will not be available.

GQG Partners LLC (UK) Ltd. is a company registered in England and Wales, registered number 1175684. GQG Partners LLC (UK) Ltd. is an appointed representative of Sapia Partners LLP, which is a firm authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) (550103).

© 2023 GQG Partners LLC. All rights reserved. Data presented as at 30 September 2023 and denominated in US dollars (US$) unless otherwise indicated.

CIOLTR 3Q23