Key Takeaways

After decades of socialism and economic stagnation, India underwent a series of reforms in the early 1990s, such as privatizing state-owned companies and encouraging private sector investment, which led to an economic boom

Following the global financial crisis, India’s reform agenda stalled and corruption scandals emerged, leading to economic stagnation and India being labeled as one of the Fragile Five emerging market economies

Since 2014, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership, India has witnessed ongoing economic reforms, aimed at reducing corruption, decreasing the government’s role in the economy, fostering private sector investment, and investing heavily in infrastructure, transforming India into a more pro-business environment

Period One: the Partial Liberalization the Indian Economy In The Early 1990s

The decades of socialism since Independence had led to a dormant economy, with a vast majority of the population in poverty. Many still remember monopolies being handed to a few cronies, resulting in long waiting lines for almost everything, from buying a two-wheeler to securing a telephone connection.

During this period, entire sectors were nationalized (such as the banking system in the early 1970s), tax rates exceeded 90 per cent for the highest earners, and corruption ran rampant. The corporate tax rate was close to 57 per cent and customs duties of 200-300 per cent were common. These economic policies stifled the country’s growth for decades; critics cruelly dubbed it the “Hindu rate of growth”. It is hard to believe now, but GDP per capita only grew at 1.3 per cent per annum over those four decades.

Eventually, India faced a major economic crisis in 1991, where the government nearly defaulted and ran out of foreign exchange reserves. This forced the hand of then Prime Minister Narasimha Rao to institute much needed reforms. Rao’s Congress administration does not get enough credit, but he was ironically the best Prime Minister the Congress party produced in its long history. The rest of them, while being adept politicians have turned out to be rather mediocre economic stewards of India.

While painful at the time, the 1991 crisis proved to be a blessing in disguise as it forced the country to adopt pro- market measures and end the License Raj. State-owned companies were privatized, the currency peg was eventually removed, private sector investment was encouraged, and the fiscal situation was stabilized. In other words, India was finally beginning to cut back on socialistic policies, resulting in an economic boom. In 2001, Goldman Sachs even named India as part of the BRIC countries expected to dominate the global economy. However, the good times did not last.

Central banks are dominating the headlines, which is not surprising given the increase in interest rates from zero, or below, during the last 15 months. ”

PERIOD TWO: THE STAGNATION POST-GFC (GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS)

Politicians seemingly forgot what had triggered the boom years – a combination of reforms and the global boom led by China. The reform agenda stalled, and in certain cases, even reversed. The incumbent party was embroiled in countless corruption scandals, including the infamous telecom scandal, where the government was accused of giving away cheap spectrum licenses in exchange for bribes. As a result, in 2013, Morgan Stanley labeled India as one of the Fragile Five emerging market economies. The August 2013 cover of The Economist captures the entire picture of what Modi inherited from the prior administration.

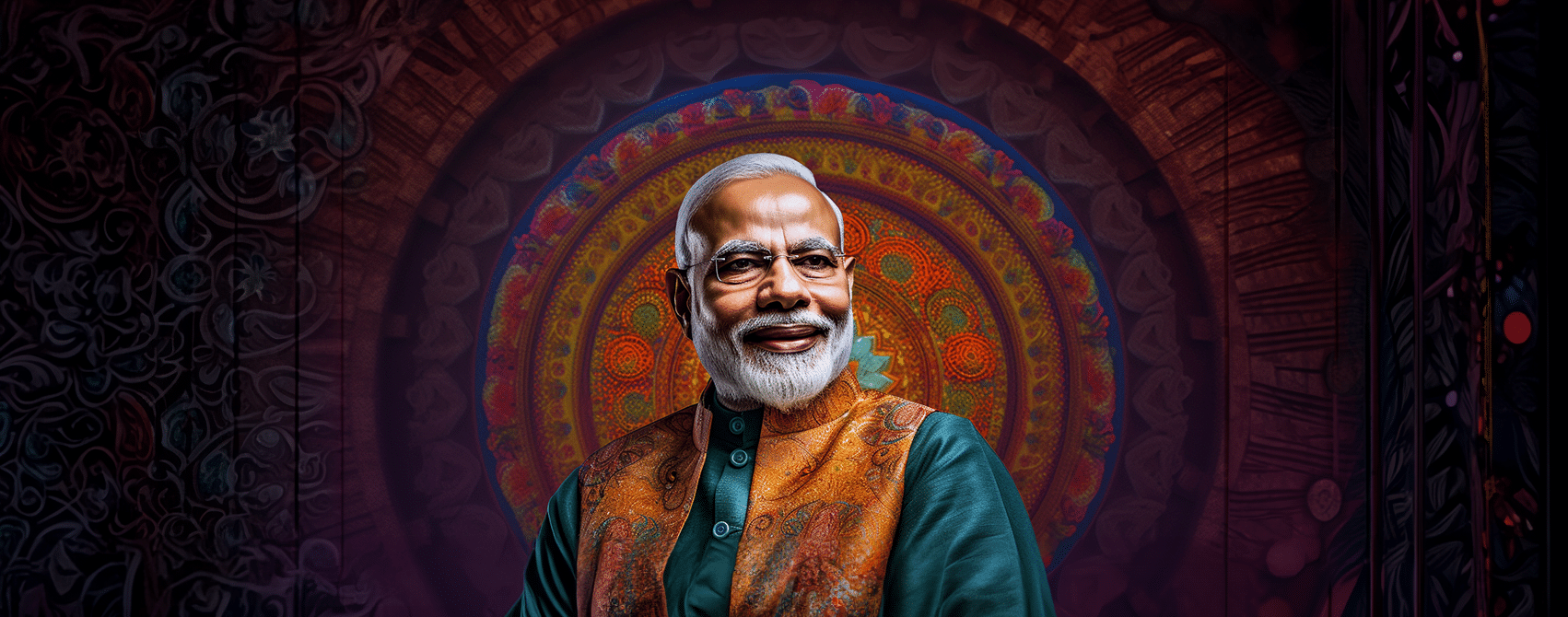

Before we proceed, we want to make it clear that this is not a political statement or endorsement. Rather, this is an attempt to objectively analyze and highlight key structural and economic policy improvements taking place in India, putting aside the political noise or controversies one may point to regarding Modi and his party. As global investors who have followed India closely, our focus at GQG Partners is to shed light on what we consider to be a major transformation that has been occurring in India and getting lost in the headlines.

PERIOD THREE: THE ONGOING REFORMS (2014-PRESENT)

Frustrated with the lack of progress, Indian voters decisively removed the incumbent party from power in the 2014 elections. Narendra Modi, the then-chief minister of Gujarat state, won the election with the promise of economic reforms. Under his leadership, Gujarat had heavily invested in infrastructure, cut red tape, and emerged as one of the most pro-business and prosperous states in India. As prime minister, he promised to replicate the “Gujarat model of development” across the country. However, he was dealt a bad hand and spent the first few years stabilizing the economy. By the time he came into office, the rupee had collapsed from 45 USD/INR in 2010 to 65 USD/INR in 2014, and the banking system was on the verge of a major crisis. A decade later, Modi has the highest approval ratings in the world by far, largely due to his economic policies.

Before we proceed, we want to make it clear that this is not a political statement or endorsement. Rather, this is an attempt to objectively analyze and highlight key structural and economic policy improvements taking place in India, putting aside the political noise or controversies one may point to regarding Modi and his party. As global investors who have followed India closely, our focus at GQG Partners is to shed light on what we consider to be a major transformation that has been occurring in India and getting lost in the headlines.

POTENTIAL IMPACT OF ECONOMIC REFORM NOT YET FULLY RECOGNIZED

While Indian voters have already recognized it, we believe that the financial markets and mainstream media have not fully grasped the long-term implications of Modi’s economic reform agenda. Given India’s sheer size (with one in every six people globally residing in India), reforms in the country will have implications for the world economy, akin to the early-2000s China boom. Despite being the fifth-largest stock market in the world at $3.5 trillion (for comparison, Germany is $2 trillion and Japan is $5 trillion), India represents less than 2 per cent of the MSCI ACWI Index and less than 15 per cent of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, partly due to quirks in the index construction that we believe are not always logical.

We have also been surprised to witness such negative media coverage on India despite the remarkable progress. Jefferies’ strategist Chris Wood attributed this lopsided coverage to the fact that most “Indian correspondents talk only to the traditionally champagne-socialist intelligentsia so visible on English language Indian TV channels…[who] have found themselves removed from all forms of influence in Delhi since Modi took power in 2014…[and] are willing to air their frustrations to anybody prepared to listen.”1 This lack of financial and media interest in India creates an attractive entry point for long-term investors in our opinion.

So Why Are Bullish on India?

As global investors, we monitor economic policies in every major country and deploy our capital accordingly. We have been increasingly disappointed with the recent policies implemented in the developed world, such as endless stimulus in both the US and Europe, regulatory crackdowns in China, and even nationalization in France. In contrast, we believe India stands out with its move to become more pro-business.

Modi’s economic framework can be boiled down to these key pillars:

Reducing Corruption and Crony Capitalism

A landmark reform was the 2016 Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, which created a framework to deal with insolvent companies. A joke among veteran Indian bankers was that corporate borrowers would travel in coach while initially securing loans, and then travel in private jets while arrogantly renegotiating loans. Those days are over; managements that renege on loans now end up forfeiting their assets and getting arrested. Similarly, the 2016 Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act has transformed the real estate sector and ensured that fraudulent real estate developers are punished and weeded out.

Reducing Government’s Role In The Economy

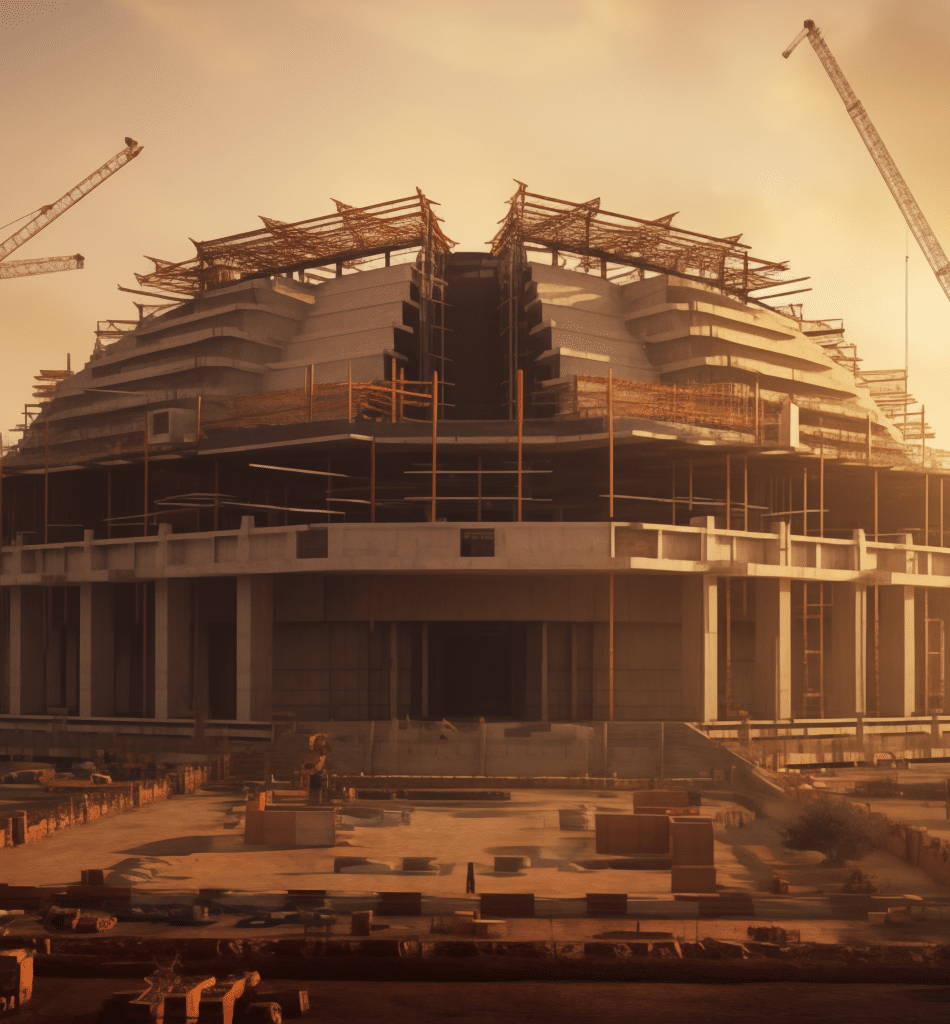

To quote Modi himself, “the government has no business to be in business.”2 We couldn’t agree more. Based on our experience investing in other emerging markets, a bloated government tends to crowd out the more efficient private sector and hurts productivity growth. For example, the Indian government recently announced the National Monetization Pipeline where it will monetize its key state-owned assets and use the proceeds to fund infrastructure development.

A good case study is Air India’s privatization.3 Air India (the second-largest Indian airline operator) was a chronically loss-making state-owned company. It cost the taxpayer approximately $1 billion annually just to keep it afloat until the government sold it to the Tata Group in 2022. Just a year later, the Tata Group placed the biggest aircraft order in India’s aviation history. This demonstrates the power of privatization: the government receives cash to deploy elsewhere, and consumers benefit from increased investment in the sector. In contrast, China is going in the opposite direction.

Fostering Private Sector Investment

Every Indian corporate we speak to mentions how much the current administration has streamlined day-to-day business, whether it is acquiring land, obtaining business permits, or bidding for projects. For example, this administration simplified India’s complicated tax policy with its landmark GST Tax Reform in 2017. This bill reduced the tax burden for businesses while still increasing government tax collections. The bill also allowed the government to eventually reduce the corporate tax rate from 30 per cent to 22 per cent in 2019.

Additionally, the government has made impressive progress on the digital front. For example, its Unified Payments Interface was launched in 2016 to facilitate digital transactions, bringing millions of Indians and small businesses into the formal economy. By some standards, India has leapfrogged many developed countries with its payments infrastructure. Similarly, India’s private sector has innovatively increased broadband access increasing 12 times in the past ten years to nearly 900 million connections. Indian consumers now enjoy first world broadband at developing world prices.